How gender and sexuality can affect political engagement in the UK.

The concept of citizenship is having equal status and accessibility to rights and this comes with responsibilities. For example, citizens pay taxes to the government in order for there to be a free National Health Service. Citizenship has encompassed a narrative that was of a heterosexuality normative agenda. The legislation of homosexual people happened in Britain in 1967. The LGBT (lesbian, Gay, Bisexual and Transsexual) Community however, have been very active in fighting for their right to have full citizenship status in, ‘education, parenting, employment, and housing’ (Richardson, 1998, pp.89) prior and since this law was introduced. Dispute the legal effort that the LGBT community have campaigned for, there are still discrimination for example hate crimes. It was only until 2014 where same-sex couples could achieved full citizenship as this meant that they were entitle to marry and the same tax credits that heterosexual couples where, ‘affecting pension rights, inheritance rights’ (Richardson,1998, pp.89). The LGBT community has fought for their right at every stage. From the right to love anyone who is an consenting adult and being able to express this by holding hands in public without being thrown into prison to whether their sexual orientation would be discriminated against if they wanted to stand for office, and be treated as fairly as the rest of the components.

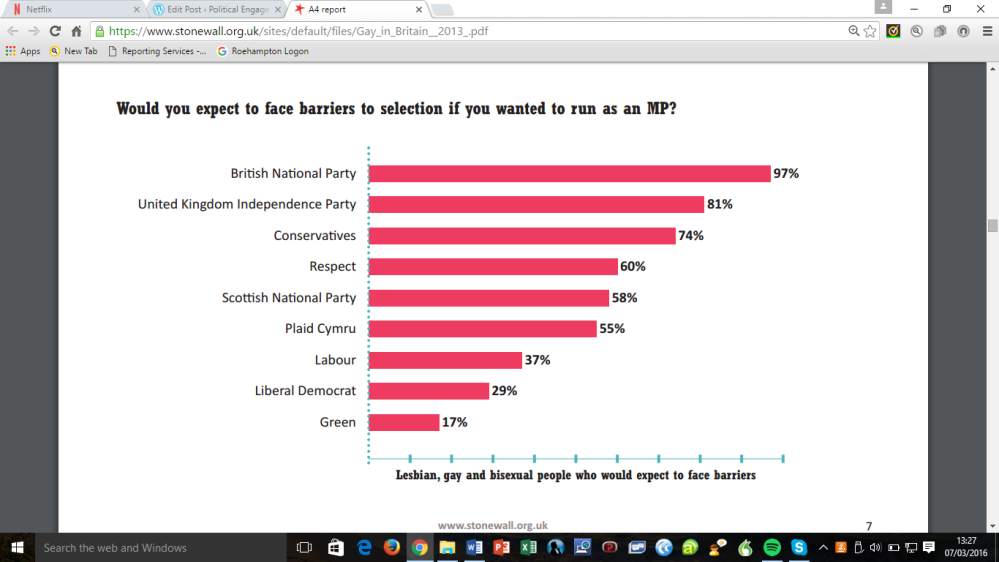

Lesbian, gay and bisexual people are under representation proportionally to the amount of people in this demographic in the House of Commons. It is said that one in ten people are gay, lesbian or bisexual and yet there are only ‘32 of the United Kingdom’s 650 MPs calling themselves gay, lesbian or bisexual’ (Shariatmadari, 2015). This may be due to the fact that there are barriers in being selected to run for an MP position, illustrated by the graph by Summerskill (2013) the Chief Executive from Stonewall.org.

(Summerskill, 2013, pp.7).

(Summerskill, 2013, pp.7).

I believe that the LGBT community are engaged in politics because of the amount of campaigning that their fellow community have done to gain equal acknowledgement from partial to full citizen status, and for the fight of LGBT rights. The limitation has been whether they have been acknowledged by government. An example is the 47 year gap from the legalization of homosexuality to the right to marry as there heterosexual friends had already based on their birth. If one is degraded as less then human or seen as the ‘other’ this makes it a lot easier to keep ‘them’ subjected. Many leaders over the years have used this tool of dehumanisation to inforce laws to segregate and oppress them from civil society. There have been examples of this many times over from; women being claimed to be less able and therefore should not have the right to vote, to Jews being seen as scum by Nazi Germans to Homosexuals being disregarded as unnatural and deviants. Full citizenship has been given in the UK to those who fit the criteria for it; heterosexual, white, middle class, and male. I would agree that with Diane Richardson, who would argue that citizenship status has been associated with the ‘institutionalisation of heterosexual, as well as male privilege’ (1998, pp.83).

An indication to male privilege would be underlined in political socialisation, and the narrative that this is gendered. Political socialisation is how we learn about politics through family, wider society and the education system. On the surface, the Electoral Commission (2005) would point out that women in general in the UK are found to be overall ‘significantly less politically active than men’, despite the fact that ‘men and women are equally as likely to vote in local, regional and national elections’. Looking deeper into the issue of women’s limited engagement in politics, the Electoral Commission (2005) found that political interest is higher among men than women (61% against 45%) and that only 31% of women feel they know at least a fair amount about politics, compared to 52% of men’. This may be due to the concept the politics is a predominantly masculine and of the male sphere, which would have been internalized by young people when learning about politics. It could be argued that this is why the ratio of male to female is at shocking levels for the twenty first Century. ‘After the 2015 General Election there are now 191 female MPs’ (Parliament, 2015) out of a possible 650. The pie chart below shows that the number of MPs in the House of Commons and their gender. Comparing the two pie charts it shows that the UK population of women proportionally is much greater than the amount of women in the current UK government. As there are ‘31 million men and 32.2 million women in the UK’ (Office for National Statistics, 2011).

![Blog 2]](https://politicalengagment.wordpress.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/02/blog-2.jpg?w=677&h=516)